Sonics Boom: My Afternoon with the Greatest Garage Band of All Time

A new documentary on The Sonics sheds some light—but not quite enough of it—on Tacoma’s favorite sons. Better still, it reignites memories of my own brief but unforgettable meeting with the band.

“Pay me that fucking money, you little shit!!”

“Fuck you, asshole!!! I’ll kick your ass!”

I sat rigid in the passenger seat, frozen in fear. Outside, in the middle of a suburban Seattle driveway, Ricky Lynn Johnson and Buck Ormsby were about to kill each other.

It was hard to believe how quickly it’d gotten out of hand. One minute, the two were settling up long-distance phone bills from a recent tour. The next they were circling each other like bar-fighters, ready to lunge for baseball bats—or worse—in the trunks of their cars. Either that or collapse right there on the blacktop, hands clutched to their hearts: Buck was 71 years old, Ricky not much less. Then, just as suddenly, it was all over. Ricky stomped off in a huff. Buck got in the car and angrily keyed the engine to life, muttering under his breath.

Just another day in the life for The Sonics, the greatest garage band of all time.

Two hours before, when Buck and I'd pulled up to Larry Parypa’s trim ranch house, the mood was light. Larry, Ricky, and Rob Lind—on guitar, drums, and sax, respectively—were already set up, jamming on an Albert King tune. After Buck introduced us, I went back to the car to grab my gear, struggling all the while to quell my jangling nerves. Because despite the optics—me and a bunch of 70-somethings goofing off in a suburban living room—this was no ordinary Saturday afternoon. Call them what you will—the best white R & B outfit, the greatest garage band, or the very first punk group—but I’d been obsessed with The Sonics for decades. And this wasn’t just a jam session, but an audition.

I’ll cut to the chase: I didn’t get the job. But I got something far more durable: The chance to spend an afternoon with my musical idols, and embark on a mini-dive into the history of Pacific Northwest rock. Here’s how it all came about.

As a dedicated lover of raw ‘60s rock and roll, I’d known about The Sonics for decades.

Like many obscure bands from the ‘60s, their backstory was largely a mystery. That’s changed in recent years; as Dan Epstein writes, a newly available documentary plumbs their story—though with mixed results. But when I learned that I shared mutual friends with Buck Ormsby, The Sonics’ manager, it ignited the slim hope I might actually cross paths with them. Though I didn’t know it at the time, the band had reunited for a single show in 2007 before undertaking a limited touring schedule.

In addition to herding The Sonics, Buck was also the bassist of The Wailers, the other leading avatars of PNW raunch rock. Because they were a bit older than The Sonics—their instrumental “Tall Cool One” was a regional hit back in 1959—The Wailers served as a kind of “big brother” band to The Sonics, much as the MC5 would for The Stooges a few years later. So when I heard through the grapevine that The Sonics needed a fill-in bass player, he agreed to take me to an informal audition.

The Sonics already had a bassist: Don Wilhelm, who’d replaced Larry Parypa’s brother Andy. But Wilhelm had a day job: He was Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s musical director. That meant that whenever Allen hosted a party at one of his numerous properties, Wilhelm was expected to be there at a moment’s notice to arrange the musical entertainment. And Allen wasn’t the type of person to keep waiting.

There was another need for a stand in: The Sonics’ singer and keyboardist, Gerry Roslie, had a history of heart trouble, and so the band needed someone who could take lead vocals on a couple of numbers to give him a break.

If you’re unfamiliar with The Sonics’ music, do yourself a favor: Immediately stop reading this and pull up their version of “Louie, Louie,” a rendition that gives the bouncy R&B number an ominous and intense grind, one not heard before or since. You’ll instantly understand two things: Why Gerry is sometimes known as “the white Little Richard,” and why there was no hope my paltry pipes could do the band justice.

That afternoon in Seattle passed by in a blur. Even though Ricky didn’t come close to replicating original drummer Bob Bennett’s primal thump, it was a dream to get to hold down the low end with one of the greatest rock bands in history. But it was when we took a break—and I got to engage in a little brain picking with the band—that my circuits really lit up.

Hilariously, the band had gathered around a desktop to watch YouTube videos of their recent shows in Scandinavia. “Wow! Listen to all those girls screaming!” exclaimed Larry as “He’s Waitin’,” perhaps the band’s single greatest song, opened the show. And I just had to find out more about this singularly raw and threatening number.

“I don’t think we ever even played it live,” said Larry. “You know, we played dances, and that’s not what people wanted to hear.” I was dumbfounded, but I had to press on. Turning to Gerry—who seemed a far gentler soul than his singing voice suggests—I asked, “What about the lyrics? I mean, they’re kind of…dark!” He looked at me mildly and said, matter-of-factly: “That’s because we’re e-vile.”

Still, it wasn’t till the rehearsal was over—and the altercation with Ricky come and gone—that I got to take a deeper dive into PNW rock history. As Buck steered us back towards Tacoma, still muttering a few choice curses at Ricky, I asked about his formative years, and discovering the rock and roll scene.

To my relief, this seemed to loosen Buck up. He explained that seeing live shows—many drawing upwards of 2,000 people to venues like Olympia’s Evergreen Ballroom or the Spanish Castle—was the thing to do on Saturday nights. A brash kid with the ability to wheedle his way backstage, Buck was eager to soak up the energy searing off the stage from artists such as James Brown and the Famous Flames, Ike and Tina, and other stars on the R&B circuit. One night in particular was a game-changer, and the moment he realized he might become more than just a bystander: Little Richard and the Upsetters, sometime in 1956.

Richard was a key inspiration for The Wailers, The Sonics, and countless other bands of the era. And for Buck, a suburban white kid, the Upsetters and their flamboyant bandleader truly were upsetting: Little Richard was a mold-breaker in nearly every possible dimension, and it was clear that even behind those matching suits, the Upsetters were some heavy dudes.

That night, Buck hunkered down in the orchestra pit at the edge of the stage, staring gape-mouthed as the band burned through their warm-up set before Little Richard joined them. Their bassist—at that point most likely Olsie "Bassy" Robinson—had seen Buck hanging around backstage before the show. After a few numbers, he looked down and asked, to Buck’s astonishment, if he wanted to play bass on a few numbers. He jumped onstage and had, as he told me, one of the formative experiences of his life.

Describing the event some 50-odd years after the fact, Buck’s face was lit by pure wonder. I felt it too: I’d been the geeky kid hanging out as close to the action as I dared, dying for a chance to show the world what I could do with a bass guitar. Robinson’s small act of kindness opened a door he might not have found on his own, and in that moment his life was changed forever.

Sidebar: Given that I’m an utter obsessive, I had to ask Buck about The Sonics’ recording techniques. As much as their standout material, it’s the sound that seems to reach out of the speakers to grab you by the throat. Many sources—including Kurt Cobain—claim that the band’s unbelievably powerful drum sound was captured by a crude dynamic mic placed more or less beside original drummer Bob Bennett’s head.

“Bullshit,” spat Buck. “That’s a load of crap!” He explained that the mic setup was actually far more sophisticated than the recordings would suggest, with top and bottom mics on the snare, front and back mics on the kick, and one or two overheads, depending on availability. The trick was to place a big piece of plywood under the kick to introduce more “liveness” to a dead room. I also learned that one secret of the band’s overdriven sound was obtained by deliberately mismatching the speaker impedances of their Fender amplifiers.

The raw, early era of rock and roll is quickly fading into memory.

Buck died on October 29, 2016—his 75th birthday. Bob Bennett passed away early in 2025. The songs that spurred a generation of teens are remembered by fewer and fewer of us, even as some of them—notably their version of Richard Berry’s “Have Love Will Travel”—find a fleeting afterlife in films and TV commercials.

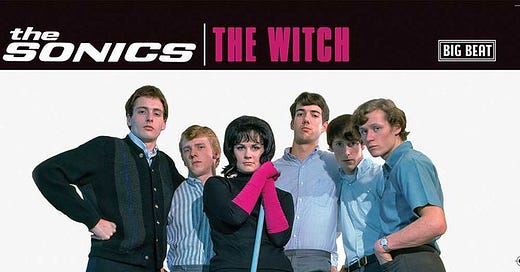

But even if the people who made that indelible art are disappearing, the art itself isn’t. Pull up “The Witch,” “Psycho,” “Cinderella,” “Strychnine” or any other of The Sonics’ blazers and hear for yourself. If they don’t make you want to move, you might already be dead yourself.

Have love will travel.

I’ve been obsessed with The Sonics since I was a teen & a Boston hardcore band called Psycho* sent their eponymous debut EP to my college station. It kicked off with a sloppy but compelling cover of, you guessed it, “Psycho”. I quickly clocked it was a cover. Somehow in pre-internet 1983 I tracked it back to its source. I was immediately smitten with my new found secret band.

As a onetime, sometime bass player of zero renown I would’ve soiled my boxers at the mere thought of sitting in with The Sonics playing triangle. Being asked to replicate Roslie’s inimitable howl? Forget it. Was fortunate to see them maybe 15 years ago in Brooklyn with The Flamin’ Groovies. Even at that late stage for both bands, it was the one of the greatest double bills I’ve seen in thousands of shows.

Finally, at the risk of overstaying my comment welcome, I read old interviews in which Roslie expressed embarrassment re: “He’s Waitin’”. That it didn’t go over live in the early days is no surprise. I’m guessing their core audience could either get off or shrug off “Strychnine” & “The Witch”. But invoking Satan back then would have been one step too far.

*Psycho was GG Allín’s backing band for a spell. Natch.